A piece of the space rock that lit up skies over England on Feb. 28 has been found.

The singed hunk of asteroid was discovered in the driveway of a house in Winchcombe, a small town in the county of Gloucestershire in southwestern England. The rock, which weighs nearly 10.6 ounces (300 grams), is the first meteorite found in the UK since 1991, experts said, and the first known carbonaceous chondrite ever discovered in the country.

Carbonaceous chondrites are especially pristine and primitive meteorites that generally contain lots of organic material, including complex molecules such as amino acids. Studying carbonaceous chondrites can shed light on the early solar system and how the building blocks of life found their way to Earth, researchers say.

Fireballs, spaceships, iguanas: 7 strange things that fell from the sky in 2020

Such study is already under way at the Natural History Museum in London, where the meteorite now resides.

“This is really exciting. There are about 65,000 known meteorites in the entire world, and of those only 51 of them are carbonaceous chondrites that have been seen to fall like this one,” Sara Russell, a meteorite scientist at the museum, said in a statement.

“It is almost mind-blowingly amazing, because we are working on the asteroid sample-return space missions Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx, and this material looks exactly like the material they are collecting,” Russell said. “I am just speechless with excitement.”

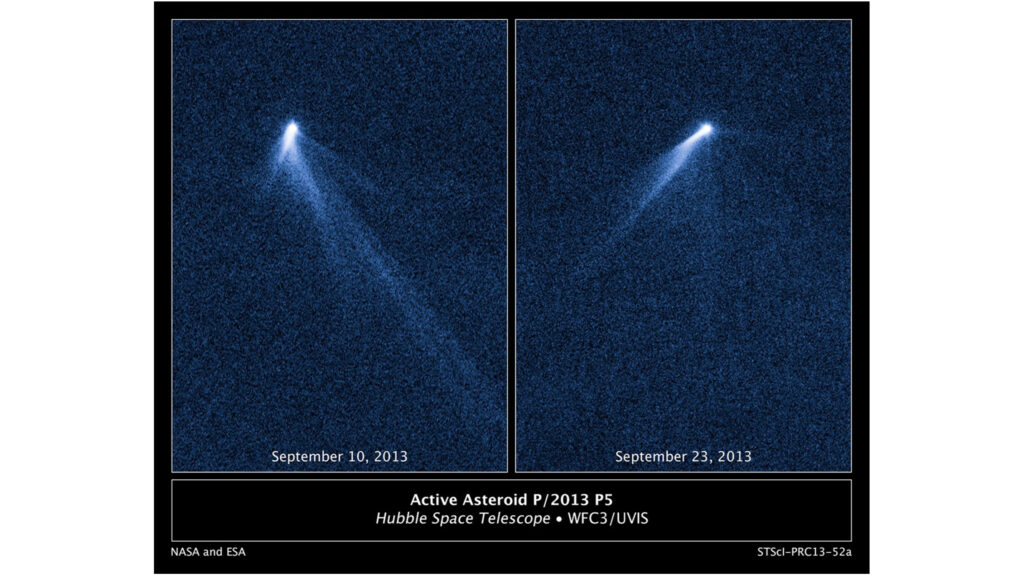

Japan’s Hayabusa2 mission returned about 0.16 ounces (4.5 g) of the asteroid Ryugu to Earth in December 2020, and NASA’s OSIRIS-REx probe collected a large sample of the space rock Bennu in October of that year. The Bennu bits will land here on Earth in September 2023, if all goes according to plan.

The newfound meteorite was spotted shortly after it came down. Residents of the Winchcombe house saw black smudges on their driveway on the morning of March 1, the day after the fireball blazed bright in England’s skies. They soon collected pieces of the space rock that had made the marks and contacted the UK Meteor Observation Network, which then got in touch with Natural History Museum personnel.

“For somebody who didn’t really have an idea what it actually was, the finder did a fantastic job in collecting it,” Ashley King, another meteorite researcher at the museum, said in the same statement.

“He bagged most of it up really quickly on Monday morning, perhaps less than 12 hours after the actual event. He then kept finding bits in his garden over the next few days,” King added. “It looks a bit like coal. It is really black, but it is much softer and is really quite fragile. It is exciting for us, because this type of meteorite is incredibly rare but holds important clues about our origins.”

The parent bodies of carbonaceous chondrites can hit Earth’s atmosphere going more than 150,000 mph (240,000 kph), King said. But the Feb. 28 fireball came in much more slowly, at “only” around 31,000 mph (50,000 kph), which explains why some pieces of the rock survived the fiery ordeal.

“The fact that it was going quite slowly, and then that it was collected so quickly after landing, avoiding any rainfall that could change its pristine composition, means that we’ve just really lucked out with everything,” he said.

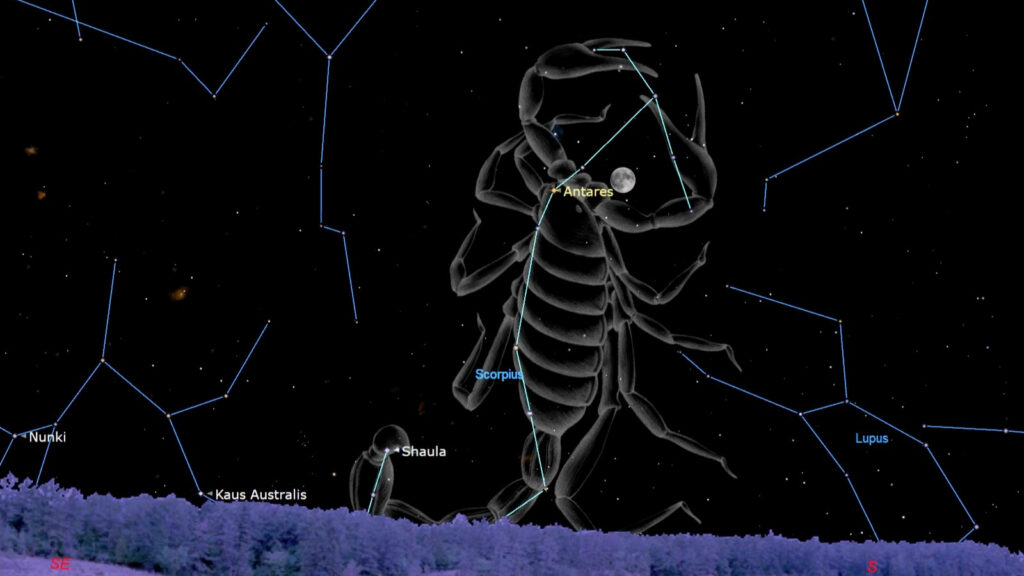

A number of fireball cameras captured the Feb. 28 event, allowing researchers to calculate a probable landing zone for meteorites and determine a rough trajectory for the parent body. These analyses indicate that the object came from the outer region of the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, scientists said.

There may well be more meteorite fragments from the Feb. 28 fireball waiting to be found. If you spot something in the Gloucestershire area that you suspect is a space rock, photograph it and record its location, Natural History Museum personnel said. Then collect a sample using a gloved hand, store the stuff in aluminum foil and contact the museum.

Mike Wall is the author of “Out There” (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.